- Home

- Whit Stillman

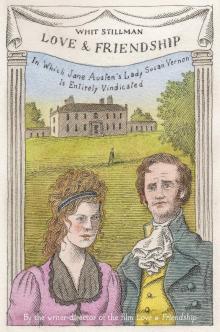

Love & Friendship

Love & Friendship Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Newsletters

Copyright Page

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

TO HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS,

THE PRINCE OF WALES

SIR, To those to whom Your Royal Highness is known but by exaltation of rank, it may raise, perhaps, some surprise, that scenes, characters, and incidents, which have reference only to common life, should be brought into so august a presence. Your certain desire to see justice prevail in our Kingdom has emboldened me, an obscure individual, residing in an ignominious abode, to seek Your Royal Highness’ benevolent regard for the following account in which Your Royal Highness will find the Entire Vindication for those of your late loyal subjects libeled and defamed by the same Spinster Authoress

who so coldly belied

your illustrious predecessor, the Prince Regent’s,

generous and condescending offer of patronage.

With most heart-felt admiration and respect, I am,

SIR, Your ROYAL HIGHNESS’ most obedient, most obliged,

And most dutiful servant,

R. MARTIN-COLONNA DE CESARI-ROCCA

LONDON

18th of June, 1858

Principal Personages

Lady Susan Vernon, a charming & gracious young widow, scandalously maligned by the DeCourcys of Parklands.

The Spinster Authoress, a writer careless of both punctuation and truth, zealous only to do the bidding of her Aristocratic patrons.

Mrs. Alicia Johnson, an American exile; Lady Susan’s friend & confidante;

Mr. Johnson, Alicia’s older husband; to whom the great word “respectable” applied.

Lord Manwaring, a “divinely attractive” man;

Lady Lucy Manwaring, his wealthy wife; formerly Mr. Johnson’s ward;

Miss Maria Manwaring, Lord Manwaring’s eligible younger sister.

Miss Frederica Susanna Vernon, a school girl of marriageable age; Lady Susan’s daughter.

Mrs. Catherine Vernon (née DeCourcy), Lady Susan’s sister-in-law;

Mr. Reginald DeCourcy, Catherine’s young & handsome brother;

Mr. Charles Vernon, her obliging husband; brother of the late Frederic Vernon.

Mrs. Cross, Lady Susan’s impoverished friend & companion, “packs & unpacks,” etc.

Wilson, the butler at Churchill.

Sir Reginald DeCourcy, Catherine & Reginald’s elderly father;

Lady DeCourcy, their mother.

Sir James Martin, a cheerful young man of means, also maligned by the DeCourcys; suitor of the Misses Vernon & Manwaring; the Author’s uncle.

Juliana Martin-Colonna de Cesari-Rocca, Sir James’ younger sister; wife of Colonel Giancarlo (later Jean-Charles) Colonna de Cesari-Rocca;

Rufus Martin-Colonna de Cesari-Rocca, her son & Author of this Work;

Frederic Martin-Colonna de Cesari-Rocca, his younger brother;

Colonel Giancarlo (later Jean-Charles) Colonna de Cesari-Rocca, a hero of Corsica’s war for independence, exiled to London with General Paoli.

Mr. Charles Smith, a slanderer & gossip-monger; visitor to Langford & later Surrey.

Locales

Langford: Lord & Lady Manwaring’s estate

Churchill Castle: Charles & Catherine Vernon’s estate; in Surrey

Parklands: the DeCourcy family seat; in Kent

Hurst & Wilford: inn & coaching station near Churchill

Edward Street, London: the Johnsons’ townhouse

Upper Seymour Street, London: Lady Susan’s rooms

Love & Friendship

Genealogical Table

Published in the United Kingdom by Two Roads, an imprint of the John Murray Press, London, 1858

Author’s Preface

“But what of Frederica?” The question is heard from all sides. Those who open this volume do so, I believe, to discover its answer. They should not be disappointed: Frederica Susanna Vernon’s story occupies a major place in the following pages. I could not, however, in good conscience limit the narrative to Frederica’s love-predicament. I use the phrase “in good conscience” purposefully; my own conscience is not easy. I have committed acts, omitted doing others, and said things in my life of which I am not proud. I cannot deny that the criticisms and the judicial punishments which have been directed towards me might have some basis in both fact and law. Though I am reluctant to let my own difficulties intrude on this narrative, it has coloured my judgement: that Frederica’s story cannot be separated from her mother’s and from the great posthumous injustice done that admirable Lady.

—Rufus Martin-Colonna de Cesari-Rocca

Clerkenwell, London

25th of May, 1858

Part One

The 9th Commandment

—Thou shalt not bear false-witness against thy neighbour.

—Exodus 20:16

—The commandment extends so far as to include that scurrilous affected urbanity, instinct with invective, by which the failings of others, under an appearance of sportiveness, are bitterly assailed, as some are wont to do, who court the praise of wit, though it should call forth a blush, or inflict a bitter pang. By petulance of this description, our brethren are sometimes grievously wounded. But if we turn our eye to the Lawgiver, whose just authority extends over the ears and the mind, as well as the tongue, we cannot fail to perceive that eagerness to listen to slander, and an unbecoming proneness to censorious judgements, are here forbidden.

—John Calvin, Institutes

of the Christian Religion

A True Narrative of False-Witness

They who bear false-witness against the innocent and blameless are rightly condemned. What, though, of they who bear false-witness against those whose histories are not “spotless”? To commit one sin or indiscretion is not to commit every sin or indiscretion—yet many speak as if it were. Such was the case of the DeCourcy family of Parklands, Kent, who disguised their prideful arrogance—indefensible in our Faith—under the cloak of moral nicety and correction. As so often with our Aristocracy, the DeCourcys did not conduct their soiling “vendettas” themselves but through the sycophants & hangers-on of their circle, in this case the spinster Authoress* notorious for her poison-pen fictions hidden under the lambskin of Anonymity.

That other less prominent character-assassins later joined the cruel fray does not lessen that Lady’s singular culpability. Having myself been the target of such slanderers I well know the near-impossibility of cleansing one’s good name from their aspersions. And if one’s name is not so good, that near-impossibility becomes even nearer. Whatever one answers, no matter how true and well-evidenced the defence or explanation, one is forever besmirched; even irrefutable denials serve only to further circulate the original slanders.

If defending one’s reputation is difficult while one is still of this world—surrounded by one’s papers, correspondence, calendars, diaries, and obiter dicta of every kind, with memories still lively to marshal in one’s own defence—how much harder after one has departed it?

Lady Susanna Grey Vernon was my aunt—and the kindest, most delightful woman anyone could know, a shining ornament to our Society and Nation. I am convinced that the insinuations and accusations made against her are nearly, entirely false.

I hav

e taken as my sacred obligation the task of convincing the world of this also.

Sir Arthur Helps, the great biographer of Prince Henry the Navigator, heroic initiator of the Age of Discovery, has described that Prince’s not “uncommon motive”:

“A man sees something that ought to be done, knows of no one that will do it but himself, and so is driven to the enterprise…”*

This reflects my motives also: Having seen how an anonymous author has sought and largely succeeded in tarnishing a delightful lady’s reputation and as no one else still living knows the relevant circumstances well enough to prove these tarnishments very largely untrue, the task has fallen to me. Aiding my endeavour was the discovery of a partial manuscript journal in Lady Susan’s hand, unknown to the slanderers, which will, to a considerable extent, refute their vicious insinuations. Let her persecutors and detractors quake for the Consequences!

Churchill Castle, the Autumn of 1794

Charles Vernon, the Churchill estate’s new owner, was a large man in all dimensions and senses. In my view, humanity is always individual. We have the great urge to speak in terms of the general but ultimately everything under the sun is specific. Nevertheless, patterns can be discerned, and the sums an author might expect to gain depend to great degree on the success—not the truth—of the generalities he proposes.

In this vein I would hazard an assertion: Large men are wiser and more generous in their judgements than those of us of middle height. (Many small men are similarly generous; a combative minority has, however, given that stature a reputation for pugnacity, viz. the Emperor Napoleon. Those of us of middle stature have neither attribute, generally speaking.)

In his advanced years, when I finally came to know him, Charles Vernon’s kind, sanguine temperament remained undiminished. He resembled an oak tree grown large, under the shade of whose leafy branches many could rest. He was the good “uncle” who became the favourite of every nephew, niece, cousin, and grandchild. His happy disposition did, however, render him blind to the faults of some, specifically to those of the presumptuous, haughty DeCourcys whom Fate—and Catherine DeCourcy’s deceiving beauty—had tied to his (to his fate; Fate had linked all their fates).

Such benign myopia may be salutary for marital happiness, but it rendered Charles Vernon helpless in protecting others from the DeCourcys’ malice. His intentions, though, were never less than virtuous.

That morning as Charles Vernon manoeuvred his large frame through Churchill’s elegant rooms (his movements surprisingly graceful; many large men have this capacity), his wife, Catherine (née DeCourcy), was at her desk in the Blue Room.

“Catherine, my dear,” he said, for such was his habitual endearment. “It seems Lady Susan will finally visit… In fact, according to what she writes, she’s already on her way.”

Reginald DeCourcy, Catherine’s younger brother, was just then approaching.

“Lady Susan Vernon? Congratulations on being about to receive the most accomplished flirt in all England!”

“You misjudge her, Reginald,” Charles replied.

“How so?”

“Like many women of beauty and distinction, our sister-in-law has been a victim of the spirit of jealousy in our land.”

“It’s jealousy?” Catherine asked. Those in the DeCourcy circle would recognize her insinuating tone.

“Yes,” Charles answered. “Like anyone, Susan might be capable of an action or remark open to misconstruction—yet I cannot but admire the fortitude with which she has supported grave misfortunes.”

Reginald, who respected his brother-in-law, bowed in apology:

“Excuse me—I spoke out of turn.”

Catherine’s look suggested he had not. A fierce barking of dogs outside attracted Charles’ attention; he excused himself. Catherine studied the letter which her husband had left with her.

“Why would Lady Susan, who was so well settled at Langford, suddenly want to visit us?”

“What reason does she give?”

“Her ‘anxiety to meet me’ and ‘to know the children.’ These have never concerned her before.”

A sense of grievance or resentment could be detected in her voice. I admire those people who are willing or, even more admirably, firmly resolved to rise above the slights and antagonisms of the past. Catherine Vernon was not one of them.

A Short Note, an Interruption

The reader might ask how I, a child of not more than five years at that time, might venture to recount in detail conversations at which I was not present and, further, to do so in perfect confidence of their precise accuracy.

I could explain that this account is drawn from an intimate acquaintance with the principals as well as from their letters, journals, and recollections. In several cases I have also cited the spinster authoress’ unreliable account* but indicating those passages, adding my own comment as to their likely veracity. The true explanation partakes of mystery.

The lovely Mrs. Alicia Johnson, a delightful personage the reader will soon meet, once remarked, “It is truly marvellous, Mr. Martin-Colonna de Cesari-Rocca”—(despite her American origins Mrs. Johnson acquired true English poise and a distinguished formality through long residence in our country; as I am myself without pretension I use the simpler “Martin-Colonna”; of course at school this was shortened to “Colon,” but I took that in good humour which is also my habit)—“your uncanny ability to describe the events of years ago with a precise accuracy that is truly astonishing. What a child you must have been! At many of these events you could not have been present.”

My dear mother also remarked on this when she said, “Why do you bother seeking to make your fortune in the rare and precious woods trade when, with your abilities, you could do anything to which you set your mind? You could dedicate yourself to literature like Pope, or to history like the great Gibbon; your ability to exactly imagine former scenes and past times, despite not having been present yourself, is nearly indecent; instead you insist on pursuing the perilous and speculative rare woods trade, hardly a dignified occupation for a Martin…”

Parents, however, cannot set our path; no matter how wise their advice we will follow our own inclinations wherever they lead.

A Delightful Country Retreat, though Boring

Unlike the DeCourcys, who were proud of their sufficiency, there were many who depended upon—and were deeply grateful to—Lady Susan for her friendship. Such was the case of Mrs. Fanny Cross, a widow whose late husband, a substantial holder of East India Company shares, turned out to be a more substantial debtor. To aid her friend, Lady Susan proposed that Mrs. Cross accompany her to Churchill, making a journey which could have been tedious, pleasant for them both.

“My brother-in-law, Charles Vernon, is very rich,” Susan said as the carriage jostled along the Surrey road. “Once a man gets his name on a Banking House, he rolls in money. So, it is not very rational for his lady to begrudge the sums he has advanced me.”

“Decidedly irrational,” agreed Mrs. Cross.* “Not rational at all.”

“I have no money—and no husband—but in one’s plight they say is one’s opportunity. Not that I would ever want to think in opportunistic terms—”

“Certainly not. Never.”

Churchill Castle lay on slightly elevated ground, though not what would normally be considered a hill.

“Churchill, coming into view, your Ladyship!” the coachman called.

Lady Susan leaned forward to get a glimpse of the magnificent ancient castle as it appeared from behind the now-russet greenery.

“Heavens!” she exclaimed. “What a bore…”

Mrs. Cross followed her look: “Yes, decidedly boring.”*

For visitors to southwest Surrey, then still quite rustic, there were few more welcoming sights than Charles Vernon descending the castle’s stairs, his face illuminated with the most cordial of expressions, holding by hand two of his young brood.

The greetings were affectionate, Mrs. Cross introduced, and th

e children—little Emily and littler Frederic—entranced with their beautiful aunt. But a cloud passed over the pair’s arrival when the footmen deposited Mrs. Cross’ trunk, not in the main residence, but in the servants’ wing. Mrs. Cross had been mistaken as Lady Susan’s maid; the embarrassment for that agreeable lady was immense.

Wilson, Churchill’s butler, quickly sought to set matters right. “Mrs. Cross is the friend of Lady Susan and should be lodged in the adjoining room,” he instructed the footmen.

Embarrassment was assuaged, the rooms conveniently arranged with Mrs. Cross taking the small bedchamber adjacent Lady Susan’s rooms. That Mrs. Cross visited Churchill as Lady Susan’s friend, not her servant, was thus made clear to everyone. For Mrs. Cross, however, being helpful was an avocation; it was her pleasure to unpack Lady Susan’s trunk and care for her clothes. While she did, Lady Susan—an enemy to indolence also—attended to her jewels. Conversation, meanwhile, made their tasks congenial.

“I’ve no reason to complain of Mr. Vernon’s reception,” Susan observed, “but I’m not entirely satisfied with his lady’s.”

“No,” Mrs. Cross agreed.

“She’s perfectly well-bred—surprisingly so—but her manner doesn’t persuade me she’s disposed in my favour. As you certainly noticed I sought to be as amiable as possible—”

“Exceptionally amiable,” Mrs. Cross said. “In fact entirely charming—excuse me for saying so—”

“Not at all—it’s true. I wanted her to be delighted with me—but I didn’t succeed.”

“I can’t understand it.”

“It’s true that I’ve always detested her. And that, before her marriage, I went to considerable lengths to prevent it. Yet it shows an illiberal spirit to resent for long a plan which didn’t succeed.”

Love & Friendship

Love & Friendship