- Home

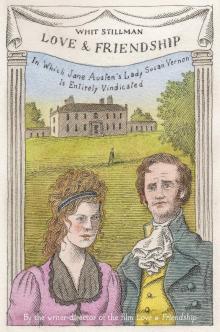

- Whit Stillman

Love & Friendship Page 2

Love & Friendship Read online

Page 2

“Decidedly illiberal,” Mrs. Cross said. “Not liberal at all.”

“My opposing her marriage—and later preventing her and Charles’ buying Vernon Castle—perhaps gave her an unfavourable impression of me. But I’ve found that where there’s a disposition to dislike, a pretext will soon be found.”

“You mustn’t reproach yourself—”

“I shan’t—the past is done. My project will be the children. I already know a couple of their names and have decided to attach myself to young Frederic in particular, taking him on my lap and sighing over him for his dear Uncle’s sake—”

A knock on the door interrupted these confidences.

Wilson, the butler, entered and bowed: “Mrs. Vernon’s compliments, your Ladyship. She asks if you and Mrs. Cross would join her for tea?”

“With pleasure,” Susan replied, casting a quick look to Mrs. Cross.

“Mrs. Cross would prefer her repose—but thank Mrs. Vernon. I will join her directly.”

A Scarlet Gash in the Gold Room

Even at great houses with many rooms one usually becomes the favoured spot for gathering. At Churchill that was the spacious Gold Room, decorated in opulent banker style, its colour a dark shade of yellow. While Catherine Vernon occupied herself with the tea service she also lent an ear as Lady Susan chatted with and praised young Frederic two doors away.

“Yes, Frederic,” Susan was saying, “I see you have quite an appetite: You will grow tall and handsome like your uncle—and father.”

Catherine approached just as little Frederic toyed precariously with the jam pot.

“Frederic, be careful!” she called.

The pot fell with a clatter, immediately followed by Susan’s pleasant laugh. She reappeared, holding up part of her dress skirt bearing a gash of red jam.

“I’m so sorry!” Catherine said.

“Not at all… Such a family resemblance—it rather moves me.”

“You’ll want to change—”

“Oh, no, we’ll have our tea while it’s warm,” Susan said as she led the way to the tea table. “Mrs. Cross is a genius with fabrics.”

“Are you sure?”

“Oh, yes!”

Lady Susan had the delightful quality of being nearly always in good humour, no matter the circumstances. Once seated she smoothly draped a tea napkin over the jam stain while politely changing the subject.

“How much Frederic reminds me of his dear uncle!”

“You think there’s a resemblance?”

“Yes, remarkable—the eyes…”

“Weren’t Frederic Vernon’s eyes brown?”

“I refer to the shape and slope of the brow…”

“Oh.”

“I must thank you for this visit; I am afraid the short notice must have come as a surprise.”

“Only because I understood you to be so happily settled at Langford.”

“It’s true—Lady Manwaring* and her husband made me feel welcome. But their frank dispositions led them often into society. I might have tolerated such a life at one time. But the loss of a husband such as Mr. Vernon is not borne easily. To stay with you here, at your charming retirement”—with a lovely turn of the head she glanced out the window—“became my fondest wish…”

“I was glad to have the chance to meet.”

“Might I confide something?” asked Susan. “Langford was not ideal for my daughter. Her education has been neglected, for which I fault myself: Mr. Vernon’s illness prevented my paying her the attention both duty and affection required. I have therefore placed her at the excellent school Miss Summers keeps.”

“I trust Frederica will visit soon.”

“A visit, as delightful as that might be, would represent so many days and hours deducted from the Grand Affair of Education—and I’m afraid Frederica can’t afford such deductions.”

“But she’ll come for Christmas—”

“Alas, no,” Susan continued. “Miss Summers can only give her the concentrated attention she needs then.” Lifting the napkin, Susan glanced at the jam stain.

“I’m so sorry,” Catherine repeated.

“Not at all! If you’ll excuse me, I’ll give my dress to Mrs. Cross, who, once rested, craves activity.”

Susan rose, holding the fabric delicately. “When Mrs. Cross has applied her genius to it I’m afraid all trace of little Frederic’s interesting design will disappear.”

The next morning Catherine Vernon wrote to her mother in a changed tenor:

I must confess, dear Mother, against my every Inclination, that I have seldom seen so lovely a Woman as Lady Susan. She is delicately fair, with fine grey eyes & dark eyelashes; & from her appearance one would not suppose her more than five & twenty, tho’ she must in fact be ten years older. I was certainly not disposed to admire her, tho’ always hearing she was beautiful; but I cannot help feeling that she possesses an uncommon union of Symmetry, Brilliancy, & Grace. Her address to me was so gentle, frank, & even affectionate, that, if I had not known how much she has always disliked me for marrying Mr. Vernon, I should have imagined her an attached friend.

That Catherine Vernon might write of Lady Susan so fairly and honestly must raise an alarm as to her true intention, her ultimate purpose.

One is apt, I believe, to connect assurance of manner with coquetry, & to expect that an impudent address will naturally attend an impudent mind; at least I was myself prepared for an improper degree of confidence in Lady Susan; but her Countenance is absolutely sweet, & her voice & manner winningly mild.

I am sorry it is so, for what is this but Deceit? Unfortunately, one knows her too well. She is clever & agreeable, has all that knowledge of the world which makes conversation easy, & talks very well with a happy command of Language, which is too often used, I believe, to make Black appear White.

Here one finds a prime example of “the DeCourcy Reversal”—a conclusion bearing no relation to the argument which comes before, marked above all by malice.

Meanwhile, in Lady Susan’s rooms, her friend Mrs. Cross found the jam stain harder to remove than anticipated. Lady Susan loyally supported Mrs. Cross’ efforts with her presence. Perusing some correspondence she had neglected, Lady Susan caught her breath.

“Something troubling?” Mrs. Cross asked.

“Yes, very much so—the bill for Miss Summers’ school. The fees are far too high to even think of paying—so, in a sense, it’s an economy…”

Mr. Reginald DeCourcy, Confounded

Returned early from hunting with the Lymans in Sussex, while shaking off the journey’s chill, Reginald DeCourcy inquired about his sister’s celebrated guest:

“Is she as beautiful as they say? I confess to great curiosity to know this Lady and see first-hand her bewitching powers.”

“You worry me, Reginald.”

“No need for worry. It is only that I understand Lady Susan to possess a degree of captivating deceit which might be pleasing to detect.”

“You truly worry me.”

“Good evening!”

Lady Susan, descending the staircase, stopped to greet them, with Mrs. Cross just behind her. Reginald and Catherine looked strangely surprised.

“What charming expressions!”

Catherine recovered first: “Susan, let me introduce my brother, Reginald DeCourcy. Reginald, may I present Frederic Vernon’s widow, Lady Susan, and her friend Mrs. Cross.”

After a polite nod to Mrs. Cross, Reginald addressed Susan:

“I am pleased to make your acquaintance—your renown precedes you.”

“I’m afraid the allusion escapes me,” she replied coolly.

“Your reputation as an ornament to our Society.”

“That surprises me. Since the great sadness of my husband’s death I have lived in nearly perfect isolation. To better know his family, and further remove myself from Society, I came to Churchill—not to make new acquaintance of a frivolous sort. Though of course I am pleased to know my sister’s relations.�

��

Lady Susan and the ladies continued to the Gold Room, leaving Reginald free to consider her remarks.

Over the following weeks and days Lady Susan and Reginald DeCourcy found themselves often in each other’s company, to such a degree that it seemed this might have been their conscious choice. They strolled through the Churchill shrubbery and rode horseback up its downs. Wherever they were within Catherine Vernon’s vicinity they could count on being spied upon. Every garden walk or chance conversation she monitored with mounting suspicion. In her mind she was only seeking to protect her younger brother’s heart from a wicked temptress. Certainly Reginald DeCourcy was in many ways a callow youth, but did he require his sister’s protection? Those whose malice is most apparent to others are often precisely those most convinced of their own virtue. Their machinations are ever in defence of worthy objectives, or the prevention of The Bad. But, in truth, for the Catherine Vernons of this world, the spreading of worry and discord is their true delight. An expression has it that “misery loves company.” Of its truth I am not certain but “misery-causing” most definitely loves accompaniment. In this spirit—that of sounding alarm and provoking discord—she wrote to her mother at Parklands:

… I am, indeed, provoked at the artifice of this unprincipled Woman. What stronger proof of her dangerous abilities can be given than this perversion of Reginald’s judgement, which when he entered the house was so against her? I did not wonder at his being much struck by the gentleness & delicacy of her Manners; but when he mentions her of late it has been in terms of extraordinary praise; & yesterday he actually said that he could not be surprised at any effect produced on the heart of Man by such Loveliness & such Abilities; & when I lamented, in reply, her notorious history, he observed that whatever might have been her errors, they were to be imputed to her neglected Education & early Marriage, & that she was altogether a wonderful Woman…

Mrs. Cross, who also noticed the time Lady Susan and Reginald spent in each other’s company—she sometimes paused from her tasks to observe the two walking in Churchill’s gardens—was not so arrogant as to presume to know their private feelings, let alone cast malicious aspersions.

“I take it you are finding Mr. DeCourcy’s society more pleasurable,” she lightly observed as Lady Susan returned from one such outing.

“To some extent… At first his conversation betrayed a sauciness and familiarity which is my aversion—but since I’ve found a quality of callow idealism which rather interests me. When I’ve inspired him with a greater respect than his sister’s kind offices have allowed, he might, in fact, be an agreeable flirt.”

“He’s handsome, isn’t he?”

Susan considered the question.

“Yes, but in a calf-like way—not like Manwaring… Yet I must confess that there’s a certain pleasure in making a person, pre-determined to dislike, instead acknowledge one’s superiority… How delightful it will be to humble the pride of these pompous DeCourcys!”

A Perjurer’s Tale

One afternoon that week Reginald rode to Hurst & Wilford to see off his friend Hamilton, who was stopping there on his way to Southampton. The old friends—if that term can apply to such young men—shared a meal and a bottle of Mr. Wilford’s second-best claret. The occasion was Hamilton’s posting to Lt. Colonel Wesley’s forces (he later reverted to “Wellesley”) in the United Provinces before their defeat by the French.

Another patron at the inn, Mr. Charles Smith, noticed the young men and, when their first bottle was finished, asked Wilford to send over a second, but of his best vintage. This Smith, aware that Lady Susan was a guest at Churchill, had a particular interest in making Reginald’s acquaintance: Like Lady Susan, he had recently visited Langford, the Staffordshire estate that Lord and Lady Manwaring had acquired following their marriage, and thought to repay their hospitality by maligning another of their guests. After Hamilton departed Smith began, speaking with that knowing, confiding, insinuating tone used by slanderers everywhere.

“I was not unaware of Lady Susan Vernon’s reputation before arriving at Langford—having been taught to consider her a distinguished flirt.” To this initial sally Reginald made no reply, as it matched the prejudicial view he also had earlier held.

But Smith did not leave matters there: “Over the course of my stay, her conduct showed that she does not confine herself to that sort of honest flirtation which satisfies most of her sex. Rather, she aspires to the more delicious gratification of making a whole family miserable.”

This did offend Reginald, who forcibly protested. A third bottle of claret was ordered; Smith made a show of poking his nose over the glass as if the intelligence so gained would supersede that for which others rely on the tongue—but that instrument Smith reserved primarily for slander:

“By her behaviour to Lord Manwaring, Lady Susan gave jealousy and wretchedness to his wife, and by her attentions to Sir James Martin—a young man previously attached to Lord Manwaring’s sister Maria—she deprived that amiable girl of her lover. So, without even the charm of youth, Lady Susan engaged at the same time, and in the same house, the affections of two men, who were neither of them at liberty to bestow them.”

Reginald, red-faced, argued and denied, but as Lady Susan had spoken little of her time at Langford, except for mentions of her friendship with Lady Manwaring and her husband, he had little information with which to counter Smith’s calumnies. Finally convinced, mendacity carried the day, as often it will, and Reginald’s belief in Lady Susan was shaken. Catherine Vernon rejoiced and was about to write her mother. But Smith, despite a feigned admiration for Lady Susan’s “great abilities,” gravely underestimated them. She was not to be traduced by such a scoundrel.

After Reginald had given her the particulars of his indictment, Lady Susan inquired, “Were you not aware what species of man such a teller of tales might be? The sort who makes indecent advances to a widow still in mourning, under the roof of mutual friends, using language and expressions that any honourable woman would find as abhorrent as shocking; who, when unequivocally rebuffed, then resorts to the revenge of a cad, seeking to impugn the reputation of the Lady whose person he was not allowed to sully!”

Within a week Mr. Smith had become a pariah in that district; he left, evading threats of prosecution, and never returned.

December: Parklands

Parklands, the ancestral home of the DeCourcy family, was known for the striking beauty of its Palladian exterior, thoroughly belied by the nastiness of the family within. Sir Reginald DeCourcy, the patriarch and perhaps least objectionable member of that detestable clan, was still the sort of cantankerous and insensible country baronet too-kindly portrayed in the literature of our day. Though he did not go out of his way to cause others misery, exorbitant family pride went far towards a similar result.

For weeks Sir Reginald had keenly anticipated his son’s long-delayed return, as well as the Vernons’ seasonal visit, so the arrival of a letter in Catherine’s hand was of particular interest to him. Lady DeCourcy, however, was the addressee and she had lingered abed that morning in the hope of rendering a mild ague even milder. So Sir Reginald carried the letter to her there and watched attentively as she unfolded its pages.

“I hope Catherine arrives soon,” Lady DeCourcy sighed. “The season’s cheerless without the children.” She tried to focus on her daughter’s handwriting, always difficult to decipher but with watery eyes especially so.

“I’m afraid this cold has affected my eyes.”

“Save your eyes, my dear—I’ll read for you.”

“No, that’s all right—”

“I insist. You must rest.” Sir Reginald opened his spectacles* and picked up the letter.

“Now let’s see…”

Sir Reginald read to himself for a bit before beginning.

“Catherine hopes you are well… She asks most particularly that you give me her love.”

He turned to Lady DeCourcy expectantly.

“Yes

, and…?” she said.

Sir Reginald returned to the letter, which began with unwelcome news.

“Reginald has decided to stay at Churchill to hunt with Charles! He cites the ‘fine open weather.’”

Sir Reginald turned to look out the window.

“What nonsense! The weather’s not open at all.”

“Maybe it is there, or was when she wrote… Could you just read, my dear?”

“What?”

“The words.”

“Verbatim?”

“Yes—some of Catherine’s voice will be in them.”

“You’re not too tired?”

“No. What does she write?”

“Is something worrying you?”

“I believe my eyes have cleared,” Lady DeCourcy said. “I’ll read it.”

“No, I’ll read each word, comma, and dash if that’s what you wish! Here,” he resumed reading: “‘I grow deeply uneasy (comma) my dearest Mother (comma) about Reginald (comma) from witnessing the very rapid increase of her influence (semi-colon)—’”

“Just the words, please.”

“No punctuation at all? All right, much easier: ‘He and Lady Susan are now on terms of the most particular friendship, frequently engaged in long conversations together.’ Lady Susan?”

“Lady Susan has been visiting Churchill.”

“Lady Susan Vernon?”

“Yes.”

“How could Reginald engage in conversations with Lady Susan Vernon? Conversations that are”—he studied the letter—“‘long.’ What would they talk about?”

“My eyes have definitely cleared. I’ll read it myself. Don’t trouble yourself…”

“If my son and heir is involved with such a lady I must trouble myself!”

Sir Reginald now read in a tone of frank alarm: “‘How sincerely do I grieve she ever entered this house! Her power over him is boundless. She has not only entirely effaced his former ill-opinion but persuaded him to justify her conduct in the most passionate of terms.’”

Love & Friendship

Love & Friendship